Summary

On the evening of November 6, 2009, I visited several residences in the area around the Nutty Brown Cafe to make an objective determination of noise impacts. Using a professional, scientific sound level meter, I measured sound levels at a residence approximately 1200 feet from the stage.

I compared the measured levels to 3 criteria for noise disturbance: The Austin Noise Ordinance; The Word Health Organizations Guidelines for Community Noise; and the German DIN 45680 standard for low-frequency noise exposure assessment. In all 3 comparisons, sound from the Nutty Brown was found to exceed criteria by substantial margins.

Introduction

In 2006 a new stage was added to the Nutty Brown Cafe near Dripping Springs, turning it into an important concert venue. Since then, people in the community have complained about the sound levels of music from the Nutty Brown, and it has become a very contentious issue. Many complaints have been made by upset neighbors, including a number of complaints filed with the TABC.

As the Nutty Brown and its neighbors are in an unincorporated area, there are no applicable noise ordinances; counties in Texas are simply not permitted to have them. The TABC, however, does have a provision for noise, as follows:

Sec. 101.62. OFFENSIVE NOISE ON PREMISES. No licensee or permittee, on premises under his control, may maintain or permit a radio, television, amplifier, piano, phonograph, music machine, orchestra, band, singer, speaker, entertainer, or other device or person that produces, amplifies, or projects music or other sound that is loud, vociferous, vulgar, indecent, lewd, or otherwise offensive to persons on or near the licensed premises.

In internet conversations on the issue, it is commonly held that residents of the new Belterra development are to blame for the complaints against The Nutty Brown. This is only partially true. In reality, residents from all of the communities surrounding the Nutty Brown have filed complaints. Contrary to popular belief, most complainants are not from California, do not live in Belterra, and have lived in the area since before 2006. In some cases, long before 2006.

Conversation on this topic is frequently emotionally charged and lacking in independent facts. It is the goal of Austin Noise to encourage objective conversation on community noise by providing scientifically based opinions and analysis and, when possible, to provide objective data. Therefore I determined that it would be in keeping with the mission of Austin Noise to perform my own measurements during a concert at the Nutty Brown and share the results publicly. I contacted some homeowners near The Nutty Brown and conducted a set of measurements the evening of Friday, November 6.

During conversations with various homeowners during the evening, they all indicated that the sound levels from the Nutty Brown were below typical that evening. This agrees with my own assessment, as I visited some of these residences to perform measurements last year and I remember the music having been louder. Nevertheless, the data collected this night shows significant noise impacts at the measurement location.

Measurement Procedure

I conducted sound level measurements using a Larson Davis model 824 ANSI Type I sound level meter. This is a very accurate, scientific instrument that I am quite familiar with. My measurements will be more reliable than those conducted by someone untrained in acoustics wielding a Type II or Type III meter, such as what you might buy from Radio Shack. My employer was kind enough to lend me the meter over the weekend for this project.

The measurement location was 1180 feet from the Nutty Brown Cafe’s stage, and significantly off-axis. By off-axis, I mean the stage was not pointing at my location. In other words, measurements taken on-axis would likely yield higher sound levels. Following the path between the stage and the measurement location, the property line of the Nutty Brown is 320 feet from the stage.

The measurement location was relatively shielded by topography from traffic noise emitted by Highway 290. This was very beneficial, as it allowed a more definite determination of noise levels caused by music from the Nutty Brown. During the measurement, it was clear by observation that music from the Nutty Brown was the dominant sound source at the measurement location.

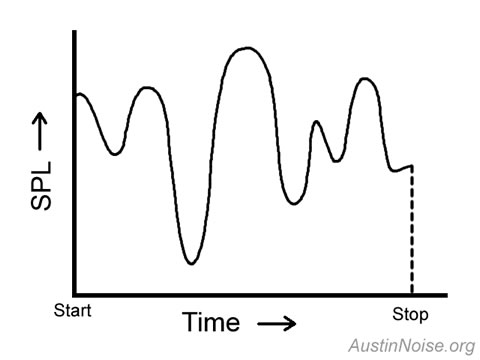

The sound level meter ran continuously through the show (except during a 20-minute period due to a depleted battery), collecting data in 5-minute intervals. Sound data was recorded in octave band, third-octave band, Leq, Lmax, Lmin, and statistical levels L1, L5, L10, L50, L90, and L99. This is a very complete set of data that Type II and Type III meters are usually not even capable of producing.

Keep in mind that this is a single set of data, collected on a single night, in a single location. A comprehensive study would include data collected on multiple nights and in multiple locations. Even so, the single set of data should be sufficient to give a good idea of the types of sound levels the Nutty Brown exposes its neighbors to.

Criteria

The applicable standard is the TABC restriction on offensive noise. In particular, sound that is “loud… or otherwise offensive to persons on or near the licensed premises.” While “loud” is a somewhat subjective term, it is still possible to make an objective determination of whether a sound can be considered “loud.”

There are many studies and standards that relate measurable sound levels to human annoyance, sleep disturbance, and hearing damage. I compare my measured levels against 3 criteria, each of which presents a different, testable version of “loud.” The selected criteria are:

- Austin Noise Ordinance – This criteria is familiar to people in the area. Also, the owner of the Nutty Brown claims to follow the Austin ordinance voluntarily. The Nutty Brown is not in city limits and therefore not required to abide by the Austin ordinance.

- World Health Organization Guidelines for Community Noise – The WHO compiled a large collection of research papers and texts on acoustics and community noise, then determined a representative set of recommended criteria for community noise regulation.

- DIN 45680 – This is a German standard for the measurement and evaluation of low-frequency noise emissions in neighborhoods. I selected this standard based on a 2005 study by P. McCullough and J. O. Hetherington that compared the relative performances of various objective noise criteria for assessing disturbance due to entertainment music. The study determined that DIN 45680 performed best at predicting subjective assessment of nuisance.

While valid arguments can be made for the appropriateness of all of these criteria (and dozens of other available criteria), the determination of what is acceptable ultimately falls under the responsibility of the TABC. I don’t know what methodology they use, or if they even have one. I would like to think that their decision process is objective, rather than political.

A secondary criterion at play comes from the Texas Penal Code, which states that once a person has been warned about creating noise, they may not produce sound in excess of “85 decibels.” The Penal Code does not define decibels, leaving its interpretation open. In acoustics, “decibels” can mean a number of things. Although it presents a numeric criterion, it will likely not come into play in the decision process of the TABC.

Nutty Brown vs Austin Noise Ordinance

To be clear, The Nutty Brown is not in the Austin city limits and not required to abide by the Austin Noise Ordinance. I make this comparison because people in the Austin area might be familiar with the ordinance, and because the owner of The Nutty Brown has stated that he voluntarily follows the ordinance in an effort to be a good neighbor.

If The Nutty Brown were within city limits, it would presumably be considered either a restaurant or a permitted outdoor music venue. You may recall that establishments such as Freddie’s and Shady Grove have struggled with the “restaurant” classification, which is held to a lower sound level limit due to a zoning restriction. We will examine both criteria.

A restaurant with live entertainment must not exceed “70 decibels,” as measured at any point along its property line. A permitted music venue must not exceed “85 decibels,” as measured at any point along its property line. The Austin ordinance defines “decibels” as sound pressure level using A-weighting and the “slow” impulse response. This translates to the Lmax value of a measurement using the slow response in dBA.

I did not measure directly at the property line. However, knowing the absolute distances between the measurement point, the property line, and the stage, it is possible to calculate sound pressure levels at the property line due to music from the stage. This has the benefit of removing the impact of traffic noise from the measured values, thereby making this method potentially more accurate than measurements taken at the actual property line.

To calculate property line noise levels, I used the method for outdoor sound propagation specified by Hoover & Keith in Noise Control for Buildings and Manufacturing Plants. This method takes frequency, atmospheric conditions (temperature and humidity), and anomalous excess attenuation into account. It is considered to be quite accurate.

Since my data was recorded in 5-minute intervals, each 5-minute period yielded a unique value for Lmax. Below are the calculated values for Lmax at the Nutty Brown property line shown against the 70 dBA and 85 dBA standards.

The lower levels between 8:55 and 9:25 represent the time between the opening act and the headlining band, while recorded music was being played over the PA. All Lmax values recorded while performers were on stage indicate exceedance of the Austin Noise Ordinance at both the 70 dBA and 85 dBA threshholds.

Nutty Brown vs The World Health Organization

The WHO publishes a set of guidelines for community noise regulation. It is based on a study of hundreds of scientific papers, texts, and standards dealing with community noise and human noise response. The set of guidelines most applicable to the Nutty Brown situation is Dwellings, which is derived from studies on sleep disturbance and human annoyance responses.

From Section 4.2.3 Sleep Disturbance Effects, of Guidelines For Community Noise:

Measurable effects on sleep start at background noise

levels of about 30 dB LAeq. Physiological effects include changes in the pattern of sleep stages,

especially a reduction in the proportion of REM sleep. Subjective effects have also been

identified, such as difficulty in falling asleep, perceived sleep quality, and adverse after-effects

such as headache and tiredness. Sensitive groups mainly include elderly persons, shift workers

and persons with physical or mental disorders.

Where noise is continuous, the equivalent sound pressure level should not exceed 30 dBA

indoors, if negative effects on sleep are to be avoided. When the noise is composed of a large

proportion of low-frequency sounds a still lower guideline value is recommended, because lowfrequency

noise (e.g. from ventilation systems) can disturb rest and sleep even at low sound

pressure levels.

Measurable effects on sleep start at background noise levels of about 30 dB LAeq. Physiological effects include changes in the pattern of sleep stages, especially a reduction in the proportion of REM sleep. Subjective effects have also been identified, such as difficulty in falling asleep, perceived sleep quality, and adverse after-effects such as headache and tiredness. Sensitive groups mainly include elderly persons, shift workers and persons with physical or mental disorders. Where noise is continuous, the equivalent sound pressure level should not exceed 30 dBA indoors, if negative effects on sleep are to be avoided. When the noise is composed of a large proportion of low-frequency sounds a still lower guideline value is recommended, because low frequency noise (e.g. from ventilation systems) can disturb rest and sleep even at low sound pressure levels…

If the noise is not continuous, LAmax or SEL are used to indicate the probability of noise induced awakenings. Effects have been observed at individual LAmax exposures of 45 dB or less. Consequently, it is important to limit the number of noise events with a LAmax exceeding 45 dB. Therefore, the guidelines should be based on a combination of values of 30 dB LAeq,8h and 45 dB LAmax. To protect sensitive persons, a still lower guideline value would be preferred when the background level is low. Sleep disturbance from intermittent noise events increases with the maximum noise level. Even if the total equivalent noise level is fairly low, a small number of noise events with a high maximum sound pressure level will affect sleep.

Therefore, to avoid sleep disturbance, guidelines for community noise should be expressed in terms of equivalent sound pressure levels, as well as LAmax/SEL and the number of noise events. Measures reducing disturbance during the first part of the night are believed to be the most effective for reducing problems in falling asleep.

From Section 4.2.7 Annoyance Responses

During the daytime, few people are seriously annoyed by activities with LAeq levels below 55 dB; or moderately annoyed with LAeq levels below 50 dB. Sound pressure levels during the evening and night should be 5–10 dB lower than during the day. Noise with low frequency components require even lower levels. It is emphasized that for intermittent noise it is necessary to take into account the maximum sound pressure level as well as the number of noise events.

These observations are combined into a set of guidelines in section 4.3.1 Dwellings

In dwellings, the critical effects of noise are on sleep, annoyance and speech interference. To avoid sleep disturbance, indoor guideline values for bedrooms are 30 dB LAeq for continuous noise and 45 dB LAmax for single sound events. Lower levels may be annoying, depending on the nature of the noise source. The maximum sound pressure level should be measured with the instrument set at “Fast”.

At night, sound pressure levels at the outside façades of the living spaces should not exceed 45 dB LAeq and 60 dB LAmax, so that people may sleep with bedroom windows open. These values have been obtained by assuming that the noise reduction from outside to inside with the window partly open is 15 dB.

To protect the majority of people from being seriously annoyed during the daytime, the sound pressure level on balconies, terraces and outdoor living areas should not exceed 55 dB LAeq for a steady, continuous noise. To protect the majority of people from being moderately annoyed during the daytime, the outdoor sound pressure level should not exceed 50 dB LAeq…

My measurements were taken near a residence, and are representative of other nearby residences. Therefore, the raw measured values can be compared directly to the criteria. Since the intruding sound is music with significant low-frequency content, the limits should be lowered. However, even without adjusting for low frequency content, the measured limits exceed these guidelines significantly, and it is not necessary to account for the nature of the sound to see that the criteria are not being exceeded.

Sleep disturbance is the more important criterion. One complaint I heard often from residents was that music from the Nutty Brown made sleep difficult, especially for children. Measured levels are compared to the WHO sleep disturbance criteria in the following chart. The dark blue line is Leq, or the time-weighted average, and should be compared to the dotted light blue line at 45 dBA. The dark green line is Lmax with the meter set to fast response, and should be compared to the dotted light green line at 60 dBA.

Both criteria for sleep disturbance were exceeded for every measured interval, sometimes by as much as 20 dB. This is based on the assumption of a partially open window. A closed window would allow for an additional 5 to 10 dB. It is not surprising, then, that residents in the area frequently complain of sleep disturbance.

Nutty Brown vs DIN 45680

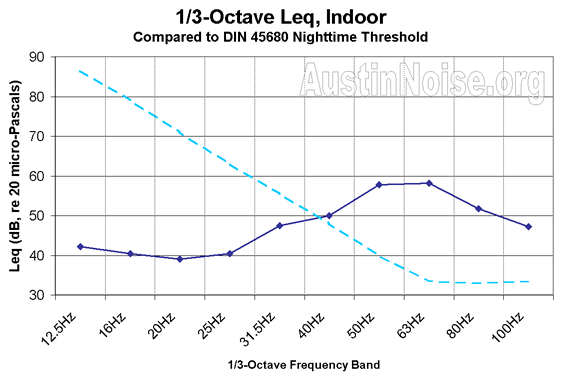

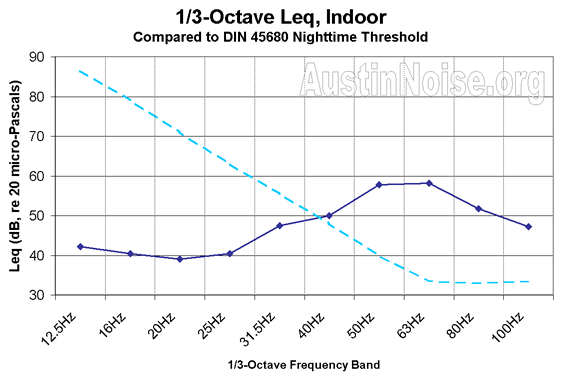

The German criterion DIN 45680 (Deutsches Institut für Norman, 1997) is frequently used to assess human annoyance due to low-frequency noise. Rather than a single A-weighted value, the criterion uses 1/3-octave values between 10 Hz and 80 Hz. The values in the curve represent the 50% auditory threshold. Measured values that exceed the criterion curve can be considered annoying or disturbing by a significant fraction of the population.

For comparison to the DIN curve, measured 1/3-octave Leq values for all intervals recorded when a performer was on the stage were combined into time-weighted averages. Those values were then reduced by 15 dB to simulate outdoor to indoor reduction through a building shell with a partially-open window (borrowed from WHO). This is a very conservative method, since residential building shells are usually more transparent to sound at such low frequencies.

The bump at 50Hz and 63Hz is very typical for live music. These are the frequencies that are responsible for the majority of complaints from people who live near music venues. Even with a conservative outdoor to indoor noise reduction estimate, the 63Hz band still exceeds the criterion by more than 20 dB.

People who live further from the Nutty Brown, such as those in Belterra, complain about low frequency noise, which permeates their houses. Reportedly, this effect occurs even several miles away. This is not unusual for outdoor venues in quiet areas and the data seems to support such claims.

Conclusions

In every test, criteria was exceeded by significant amounts. Even the Austin Noise Ordinance, which is heavily skewed to favor the noise source, was exceeded by at least 5 dB at a point over 300 feet from the stage. For all tests, conservative assumptions and methods for estimation and calculation were used. A more comprehensive analysis would likely determine greater impacts.

Comparing the measured levels to all 3 criteria suggests that noise from the Nutty Brown is not just loud, but very loud. In my professional experience, I don’t recall ever seeing this level of noise impact at a residence from a music venue over 1000 feet away.

With or without my personal interpretations, the data is clear and presented here for use in the discussion by anyone who would like to use it. Also, I will be happy to share any portion of my data or perform comparisons to additional criteria at anyone’ s request.