I should have started this blog one year earlier, as the LMTF presented their findings and recommendations back in November. Nevertheless, it can’t do any harm to share my thoughts on the Live Music Task Force Report.

From an acoustics standpoint, the most important section in the report is Sound Enforcement & Control Subcommittee Recommendations. Some of the writing in this section shows a true disconnect from actual, acoustical science. Let’s examine:

1. CITY STAFF POSITION. Creation of a staff (or contract) position within the MD responsible for managing outdoor live music sound control and attenuation.

a. Structure. The individual selected to fill the position should report to the newly created Music Department and should, ostensibly, possess substantial experience and expertise in live music engineering, acoustics, and sound attenuation.

b. Responsibilities:

i. Train and qualify sound engineers working at Austin’s outdoor live music venues;

ii. Work with outdoor venues and neighborhoods to explore ways to attenuate sound;

iii. Establish and implement “sound engineer certification program” which will teach and certify sound engineers employed by outdoor music venues;

At outdoor venues that have had acoustical engineers develop noise control, there is usually a microphone at a strategic location in the venue measuring the sound level, which is displayed on a small readout near the mixer. There is a number written next to that readout representing the maximum allowable sound level and anyone operating the board knows that the number on the readout should not exceed the written number. This does not require special training or qualification.

Assuming the physical orientation of the venue does not change and the microphone has been put into a reasonable location, the relationship between sound levels at the microphone and sound levels at the neighbor’s will not change. An acoustical engineer can spend a few hours determining what the sound level at the microphone should be to prevent excessive sound at the neighbor’s property, and that number is written next to the display. No full time personnel is needed; no special trainers are needed. Just a small contract with an acoustical consultant.

iv. Explore the most appropriate ways to measure music frequencies (as opposed to the current method of measuring decibel levels).

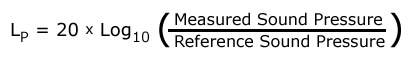

I am very happy to see the LMTF recognizing the difference between music and other noise sources, and understanding that there can be better ways to measure and quantify the loudness of music. However, the language here is cringe inducing. The term “decibel level” has, unfortunately, worked its way into the vernacular. It’s a term that is meaningless without being defined. The term “music frequencies” is also pretty bad.

The most appropriate way to measure “music frequencies,” or any other kind of sound, is with a sound level meter. Modern sound level meters all measure sound divided into frequencies or added into single number metrics such as A-weighted decibels (dBA). dBA is what people generally mean when they say “decibel level.”

There’s no shame in not understanding acoustics. It’s a complicated science and the terminology specific to acoustics doesn’t really come up in daily life. What is unacceptable is producing official documents based on incorrect or nonexistent principles.

2. SOUND ENGINEERS AT OUTDOOR LMVs. Recommend amending the appropriate ordinances to require all outdoor LMVs offering live, outdoor amplified music to utilize (i.e. hire or otherwise arrange for the services of) a city-approved sound engineer. The MD should determine, based on the size of the venue, the PA system, and other relevant factors including residential complaint history, what the standards for sound engineers should be. On a case-by-case basis, the MD may determine that this requirement may be waived. The ordinance should include penalties that require venues to stop music performances if certified engineers are not on site during performances of amplified music at venues where they are required.

Acoustical engineers are already professionally trained, qualified, and equipped to analyze a music venue based on size and sound equipment. We have at least three acoustical engineering firms in Austin. Simple technology that is easily purchased and installed by the right people can perform the same duties as the Sound Engineers proposed by the LMTF. There is no reason to hire and train full time people to accomplish tasks which can be performed as-needed by consultants.

3. CONSTRUCTION STANDARDS, INCENTIVES & BEST PRACTICES.

a. Recommend appropriate City departments and Austin Energy jointly explore and develop construction methods that reduce and improve sound attenuation at outdoor venues.

b. Recommend the City require all future Central Business District (CBD) commercial venues to adhere to enhanced construction methods that include improving acoustical insulation and soundproofing.

These are great ideas and, if implemented, would put Austin in the position of setting a good example. With the new Comprehensive City Plan in the beginning stages, we have an excellent opportunity to incorporate construction standards related to noise into the long-term planning of the city. I support these recommendations 100%.

c. Recommend adding sound control to the density bonus list to entice developers in the CBD to construct in a manner that better insulates residential projects from nearby venues.

Another good idea.

Noise control is most beneficial and cost effective when it is done proactively. Proper building construction and simple space planning are the best ways to control noise. In architectural acoustics there is a rule of thumb that states costs to fix a noise problem are 10 times what costs would have been to prevent it.

California has “Title 24” for multi-family housing projects. Part of Title 24 declares that any new multi-family building needs to be analyzed for sound exposure and be constructed to ensure appropriate indoor noise levels. This is not a new idea, but it is a good one and could fit quite nicely into the comprehensive city plan.

d . Recommend requiring future CBD residential projects to notify all tenants, before execution of lease or sale or property, of all the nearby live music venues and ask tenants to sign an acknowledgement of the nearby venues and to acknowledge that live music might be heard within a residence given their proximity.

This I can take or leave. Perhaps, rather than notify prospective tenants of specific venues, they should be made aware of what kind of district they’ll be living in in terms of the noise ordinance. That way there’s flexibility for venues coming and going during a tenants stay.

Still, though, it sounds like this is asking new tenants to sign away their right to a reasonably quiet home environment. Perhaps this stems from the common misconception that most noise complaints are generated by the people moving into the downtown condos. “Those damn Californians who are ruining Austin.” Everything I’ve read points to single family homes in Zilker and Bouldin occupied by long-time Austin residents as the true culprits. But that’s starting to get pretty far off topic.

Sections 5 and 6 are about modifying the complaint process and starting a database to accumulate and analyze the characteristics of noise complaints over long periods of time. These are good ideas, if implemented properly.

The next important section is about non-live music:

7. PROHIBITION OF AUDIBLE NON-LIVE MUSIC. Recommend the City amend appropriate ordinances to prohibit outdoor non-live music (i.e. prerecorded music, radios, television, etc.) from being audible to a single family residential property, including penalties for violation. The MD should establish a definition for non-live music, and in the interest of respecting their contribution to the live music community, include DJs within the definition of live music. Also, non-live music must conform to existing sound ordinances that regulate sound audible to residences.

Sadly, more bad acoustics shows up here. The term “audible” should be used with great caution in legal documents. “Audible” is very subjective, and inaudibility can, for certain sounds, be impossible to attain. The human ear is an amazing machine; people can hear, recognize, and understand sounds which are actually below ambient noise levels. What’s audible to a person is not the same as what’s audible to a sound level meter.

Also, I take offense at the protection this paragraph offers to single family residential property, as if dwellers of multiple family properties are not entitled to the same protections. What’s is the reasoning for this?

The remainder of the report concerns politics and financing, which is beyond the scope of austinnoise.org (for the time being).

In summary, the LMTF was clearly well-meaning and came up with some good ideas. My hope is that experts in acoustics are consulted before any changes or decisions are implemented. I would also hope that, in the future, any task forces or advisory committees take the time to educate themselves on the concepts they’re using to make decisions. A decision made based on bad information is likely to be a bad decision.